Today let us take a look at the Keynesian economic theory and how it applies to the causes and end of the Great Depression. Just a quick note about the theory, in its simplest form it states that changes in a component of spending, whether investment, consumption, or governmental, causes output to change. When looking at the Great Depression, the focus will start with investment but then move to government spending.

Companies during the 1920s rode high on the immense investment boom that took place. As stock levels began to reach a level desired by the companies, new investments were not needed. Thus, investments were cut back. With the stock market crash in 1929, investments were sent to even lower levels as companies lost confidence.

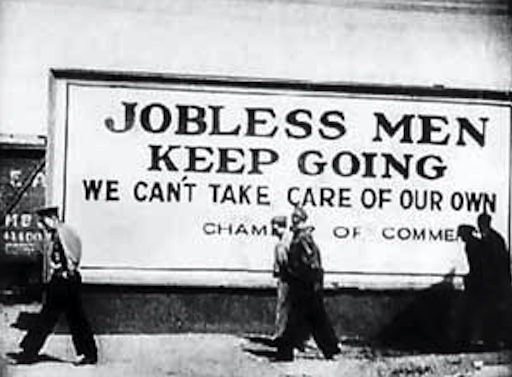

While the crash reduced wealth of some, what it did do was push the panic button for even more people. Consumption slowed as consumer confidence continued to dwindle. This hurt businesses even more. And one of the aspects of Keynesian economics was that it focused on demand, rather than supply as many had before. With the lower demand came lower tax revenues.

Governments responded by raising taxes, including an income tax doubling in 1932 as tax revenues continued to plumet. This again only stifled consumer spending putting the hurt once again on businesses. [1]

In 1930, the US government did not do the economy a favor when it passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. This raised tariffs on incoming products overseas where in turn foreign countries did the same to American goods. This only led to a decrease in demand of American goods overseas. Once again hurting American businesses with lower demand for products.

Bank Failures

In addition to falling demand, the Fed did no one any favors by not acting quickly enough to save banks from failure. From 1929 to 1933 one-third of all US banks failed. With the lack of action, the Fed only contributed to the issue at hand. However, John R. Walter suggests that perhaps many of these bank failures were inevitable due to the sheer number, or as he puts it, a shakeout.

As seen in his graph, the sheer number of banks exploded in the early 1900s as many were formed in small towns and farming communities. Walter points out, the number of banks outgrew the economic growth and became overbuilt. As more and more competitors appear in the industry, loan standards can sometimes be driven down as banks try to remain profitable for its investors. As profits continued to decline in the smaller banks, Walter shows us that 74% of the smallest banks (under $150,000 in assets) had weak profits (6% or less) compared to just 21% for larger banks (over $50 million in assets) between 1926 and 1930. [2]

As Natacha Postel-Vinay shows us in Chicago, a lot of the banks that dealt in mortgages were quick to fail. This was due to the liquidity issues of the mortgages that the banks held, not the quality. Being unable to liquidate the mortgages in a timely manner to cover the massive amounts of withdrawals that were happening, forced many banks in Chicago to shut their doors. [3]

New Deal

With confidence low, job losses mounting, and demand historically low, the economy was in disarray as President Franklin Roosevelt turned to his New Deal in an effort to stimulate the economy. As FDR attempted to provide “relief, recover, and reform” through the New Deal. As Fishback points out funds were distributed in a very political way. Some programs, such as the Agricultural Adjustment Act leaned a little more toward political sway as funds were sent to areas with large farms and with members of the Agriculture Committee in the House. However, not every program was as political. Control of the funds was a critical measure that Congress used in its favor. By using funds in swing districts or in areas with high electoral counts, the Democrats kept control of the White House and Congress. And as new legislation passed giving the executive branch more powers, eventually it had the ability to distribute the funds any way it saw fit, politics or not. [4]

J.R. Vernon argues that the US finally restored full-employment output in 1942 after 12 years of below-full-employment performance and it was all due to World War II fiscal policies. He argues against the claims of Romer and others in that the economy had almost fully recovered just prior to the war and the war just pushed it over the last hurdle. [5]

[1] “House’s Rates Increased,” New York Times, April 28, 1932, 1.

[2] John. R. Walter, “Depression-era Bank Failures: The Great Contagion or the Great Shakeout?” Economic Quarterly – Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond 91, no. 1 (January 2005): 39-42, 44.

[3] Natacha Postel-Vinay, “What Caused Chicago Bank Failures in the Great Depression? A Look at the 1920s,” The Journal of Economic History 76, no. 2 (June 2016): 478-479.

[4] Price Fishback, “The Newest on the New Deal,” The Journal of the Economic & Business History Society (June 2018): 7-8.

[5] J.R. Vernon, “World War II Fiscal Policies and the End of the Great Depression,” The Journal of Economic History 54, no. 4 (December 1994): 850, 866-867.